What Are The Makeups Of Protein

Describe the structure and part proteins

Proteins are polymers of amino acids. Each amino acid contains a central carbon, a hydrogen, a carboxyl group, an amino group, and a variable R group. The R grouping specifies which course of amino acids it belongs to: electrically charged hydrophilic side chains, polar but uncharged side bondage, nonpolar hydrophobic side chains, and special cases.

Proteins have dissimilar "layers" of construction: master, secondary, tertiary, quaternary.

Proteins have a multifariousness of office in cells. Major functions include interim every bit enzymes, receptors, transport molecules, regulatory proteins for gene expression, and and then on. Enzymes are biological catalysts that speed upwards a chemical reaction without existence permanently contradistinct. They have "active sites" where the substrate/reactant binds, and they can be either activated or inhibited (competitive and/or noncompetitive inhibitors).

Learning Objectives

- Demonstrate familiarity with monomeric units of proteins: amino acids

- Define the different layers of protein structure

- Identify several major functions of proteins

Amino Acids

Proteins are one of the most abundant organic molecules in living systems and have the most diverse range of functions of all macromolecules. Proteins may be structural, regulatory, contractile, or protective; they may serve in transport, storage, or membranes; or they may be toxins or enzymes. Each cell in a living system may incorporate thousands of proteins, each with a unique function. Their structures, like their functions, vary greatly. They are all, even so, polymers of amino acids, bundled in a linear sequence.

Effigy 1. Amino acids have a central asymmetric carbon to which an amino group, a carboxyl group, a hydrogen atom, and a side chain (R group) are attached.

Amino acids are the monomers that make upwards proteins. Each amino acrid has the aforementioned central structure, which consists of a central carbon atom, besides known as the alpha (α) carbon, bonded to an amino grouping (NH2), a carboxyl group (COOH), and to a hydrogen atom. Every amino acrid besides has another atom or group of atoms bonded to the cardinal cantlet known equally the R group (Figure 1).

The proper noun "amino acid" is derived from the fact that they comprise both amino group and carboxyl-acrid-group in their basic construction. As mentioned, at that place are 20 amino acids nowadays in proteins. X of these are considered essential amino acids in humans because the human body cannot produce them and they are obtained from the diet.

For each amino acrid, the R group (or side chain) is unlike (Figure 2).

Practise Question

Figure 2. There are 20 mutual amino acids normally found in proteins, each with a unlike R grouping (variant group) that determines its chemical nature.

Which categories of amino acid would you lot expect to find on the surface of a soluble protein, and which would y'all await to observe in the interior? What distribution of amino acids would yous look to find in a protein embedded in a lipid bilayer?

Show Answer

Polar and charged amino acrid residues (the remainder afterward peptide bond formation) are more likely to be found on the surface of soluble proteins where they can interact with water, and nonpolar (e.g., amino acrid side chains) are more probable to be found in the interior where they are sequestered from water. In membrane proteins, nonpolar and hydrophobic amino acid side chains acquaintance with the hydrophobic tails of phospholipids, while polar and charged amino acid side chains interact with the polar head groups or with the aqueous solution. Even so, there are exceptions. Sometimes, positively and negatively charged amino acid side chains interact with one another in the interior of a protein, and polar or charged amino acrid side chains that collaborate with a ligand tin can be found in the ligand bounden pocket.

The chemical nature of the side chain determines the nature of the amino acrid (that is, whether it is acidic, bones, polar, or nonpolar). For example, the amino acid glycine has a hydrogen atom as the R group. Amino acids such as valine, methionine, and alanine are nonpolar or hydrophobic in nature, while amino acids such as serine, threonine, and cysteine are polar and accept hydrophilic side chains. The side chains of lysine and arginine are positively charged, and therefore these amino acids are also known as basic amino acids. Proline has an R group that is linked to the amino group, forming a ring-similar construction. Proline is an exception to the standard structure of an animo acid since its amino group is not dissever from the side chain (Figure ii).

Amino acids are represented by a single upper case letter or a three-letter of the alphabet abbreviation. For example, valine is known by the letter V or the three-letter of the alphabet symbol val. Just every bit some fatty acids are essential to a diet, some amino acids are necessary as well. They are known every bit essential amino acids, and in humans they include isoleucine, leucine, and cysteine. Essential amino acids refer to those necessary for construction of proteins in the trunk, although not produced by the body; which amino acids are essential varies from organism to organism.

Figure iii. Peptide bond formation is a dehydration synthesis reaction. The carboxyl group of ane amino acrid is linked to the amino group of the incoming amino acrid. In the process, a molecule of h2o is released.

The sequence and the number of amino acids ultimately determine the protein's shape, size, and function. Each amino acrid is fastened to another amino acrid past a covalent bond, known as a peptide bond, which is formed past a dehydration reaction. The carboxyl group of 1 amino acid and the amino grouping of the incoming amino acid combine, releasing a molecule of water. The resulting bail is the peptide bond (Figure 3).

The products formed by such linkages are called peptides. Every bit more amino acids join to this growing chain, the resulting concatenation is known every bit a polypeptide. Each polypeptide has a costless amino group at one end. This end is chosen the N terminal, or the amino last, and the other end has a gratis carboxyl grouping, too known every bit the C or carboxyl final. While the terms polypeptide and protein are sometimes used interchangeably, a polypeptide is technically a polymer of amino acids, whereas the term protein is used for a polypeptide or polypeptides that take combined together, frequently have bound non-peptide prosthetic groups, take a singled-out shape, and have a unique office. After protein synthesis (translation), about proteins are modified. These are known as post-translational modifications. They may undergo cleavage, phosphorylation, or may require the add-on of other chemic groups. Only after these modifications is the protein completely functional.

The Evolutionary Significance of Cytochrome c

Cytochrome c is an important component of the electron transport chain, a part of cellular respiration, and it is normally found in the cellular organelle, the mitochondrion. This protein has a heme prosthetic group, and the central ion of the heme gets alternately reduced and oxidized during electron transfer. Considering this essential protein's role in producing cellular energy is crucial, it has inverse very piddling over millions of years. Protein sequencing has shown that at that place is a considerable amount of cytochrome c amino acrid sequence homology among different species; in other words, evolutionary kinship can be assessed by measuring the similarities or differences amid various species' DNA or protein sequences.

Scientists have determined that human cytochrome c contains 104 amino acids. For each cytochrome c molecule from dissimilar organisms that has been sequenced to date, 37 of these amino acids appear in the aforementioned position in all samples of cytochrome c. This indicates that in that location may have been a mutual ancestor. On comparing the human and chimpanzee protein sequences, no sequence difference was found. When man and rhesus monkey sequences were compared, the single divergence plant was in one amino acrid. In another comparing, human to yeast sequencing shows a difference in the 44th position.

Protein Construction

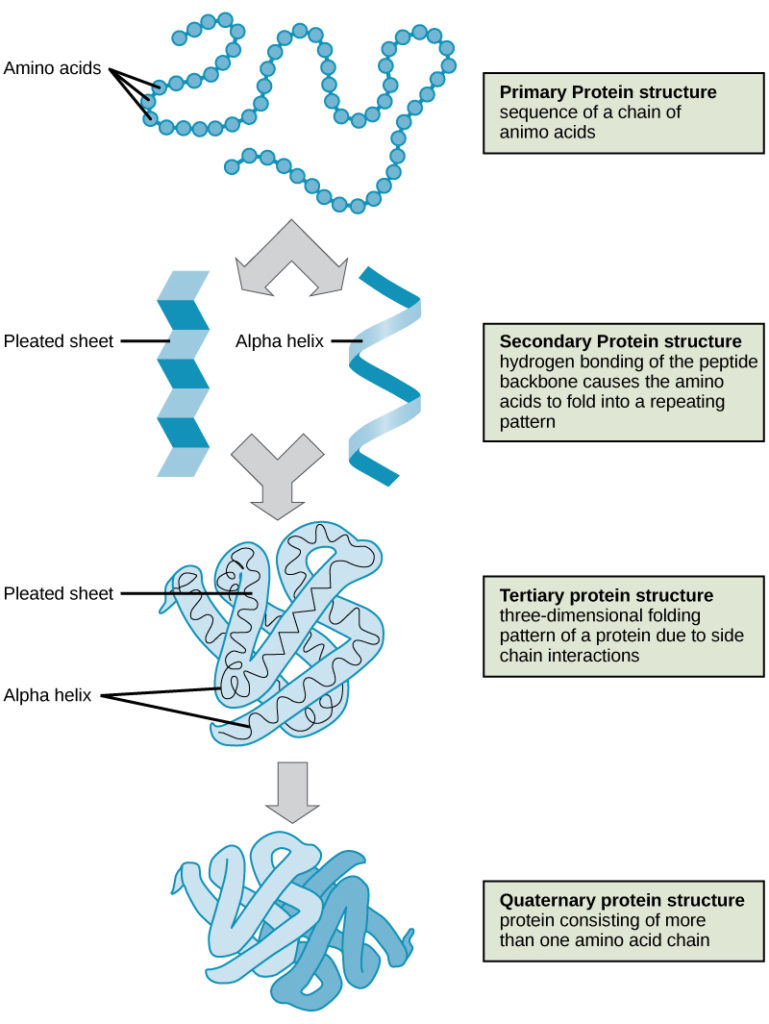

Every bit discussed earlier, the shape of a protein is disquisitional to its part. For example, an enzyme can bind to a specific substrate at a site known as the active site. If this active site is contradistinct considering of local changes or changes in overall protein structure, the enzyme may be unable to bind to the substrate. To empathise how the protein gets its final shape or conformation, we need to sympathize the four levels of protein construction: primary, secondary, tertiary, and 4th.

Principal Structure

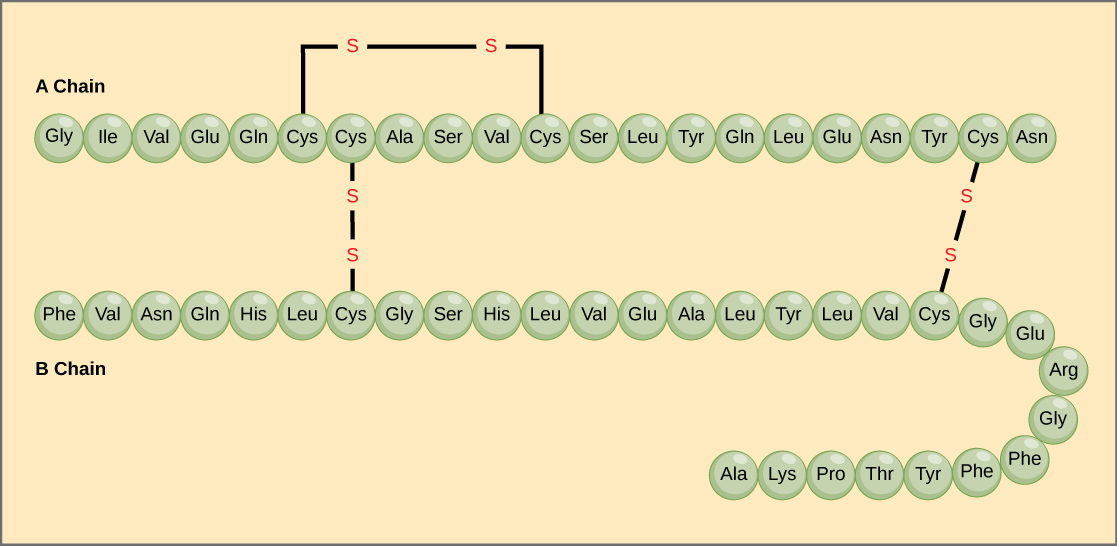

The unique sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain is its primary structure. For example, the pancreatic hormone insulin has two polypeptide chains, A and B, and they are linked together by disulfide bonds. The N terminal amino acid of the A chain is glycine, whereas the C last amino acid is asparagine (Figure 4). The sequences of amino acids in the A and B chains are unique to insulin.

Effigy 4. Bovine serum insulin is a protein hormone made of two peptide chains, A (21 amino acids long) and B (30 amino acids long). In each chain, primary structure is indicated by 3-letter abbreviations that represent the names of the amino acids in the order they are present. The amino acid cysteine (cys) has a sulfhydryl (SH) group every bit a side chain. Two sulfhydryl groups can react in the presence of oxygen to form a disulfide (S-S) bond. Two disulfide bonds connect the A and B bondage together, and a 3rd helps the A chain fold into the correct shape. Annotation that all disulfide bonds are the aforementioned length, but are fatigued dissimilar sizes for clarity.

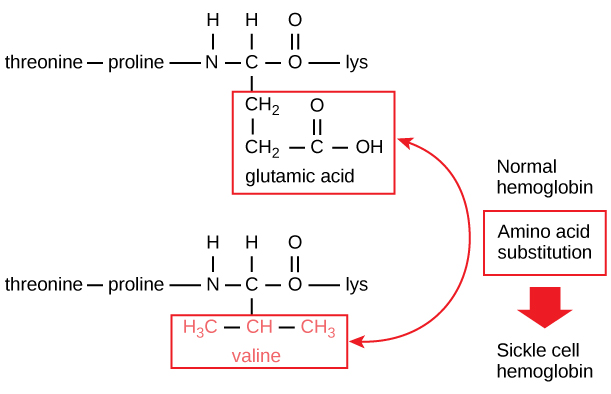

The unique sequence for every protein is ultimately determined past the gene encoding the protein. A change in nucleotide sequence of the gene'due south coding region may lead to a dissimilar amino acid beingness added to the growing polypeptide concatenation, causing a alter in protein structure and function. In sickle cell anemia, the hemoglobinβ chain (a modest portion of which is shown in Figure v) has a unmarried amino acid commutation, causing a alter in poly peptide structure and function.

Figure five. The beta chain of hemoglobin is 147 residues in length, still a unmarried amino acrid substitution leads to sickle cell anemia. In normal hemoglobin, the amino acid at position seven is glutamate. In sickle cell hemoglobin, this glutamate is replaced by a valine.

Specifically, the amino acid glutamic acid is substituted by valine in the β chain. What is nearly remarkable to consider is that a hemoglobin molecule is made upwards of 2 blastoff chains and ii beta bondage that each consist of well-nigh 150 amino acids. The molecule, therefore, has near 600 amino acids. The structural difference between a normal hemoglobin molecule and a sickle prison cell molecule—which dramatically decreases life expectancy—is a single amino acrid of the 600. What is even more remarkable is that those 600 amino acids are encoded past three nucleotides each, and the mutation is acquired by a single base change (betoken mutation), 1 in 1800 bases.

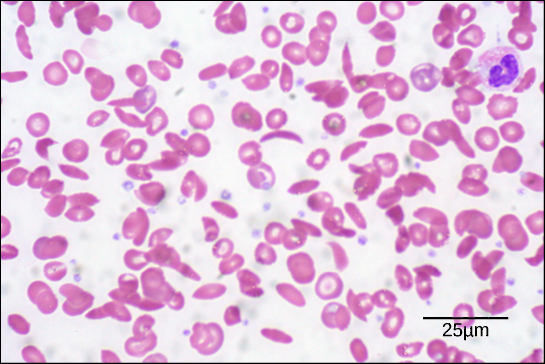

Figure six. In this blood smear, visualized at 535x magnification using vivid field microscopy, sickle cells are crescent shaped, while normal cells are disc-shaped. (credit: modification of work by Ed Uthman; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

Because of this change of i amino acid in the concatenation, hemoglobin molecules form long fibers that misconstrue the biconcave, or disc-shaped, blood-red blood cells and assume a crescent or "sickle" shape, which clogs arteries (Effigy six). This can atomic number 82 to myriad serious health bug such equally breathlessness, dizziness, headaches, and abdominal pain for those affected by this disease.

Secondary Construction

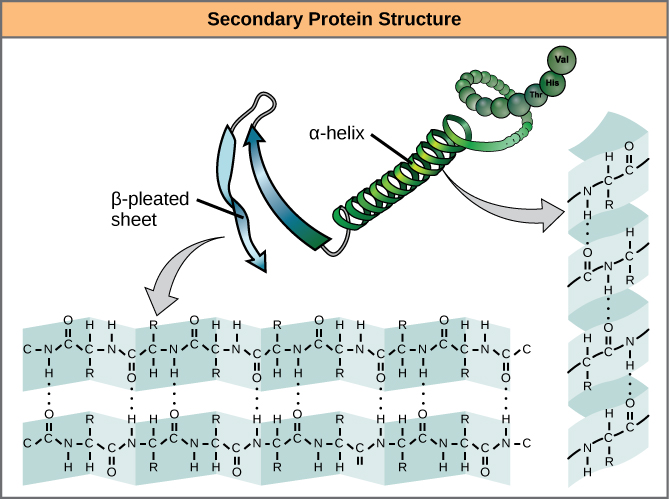

The local folding of the polypeptide in some regions gives rise to the secondary construction of the poly peptide. The most common are theα-helix and β-pleated sheet structures (Figure 7). Both structures are the α-helix structure—the helix held in shape by hydrogen bonds. The hydrogen bonds course betwixt the oxygen cantlet in the carbonyl group in one amino acid and another amino acid that is iv amino acids further along the chain.

Figure 7. The α-helix and β-pleated sheet are secondary structures of proteins that form because of hydrogen bonding betwixt carbonyl and amino groups in the peptide backbone. Certain amino acids have a propensity to course an α-helix, while others accept a propensity to form a β-pleated sheet.

Every helical turn in an alpha helix has 3.6 amino acid residues. The R groups (the variant groups) of the polypeptide protrude out from theα-helix chain. In the β-pleated canvas, the "pleats" are formed by hydrogen bonding between atoms on the courage of the polypeptide chain. The R groups are attached to the carbons and extend above and beneath the folds of the pleat. The pleated segments marshal parallel or antiparallel to each other, and hydrogen bonds form between the partially positive nitrogen atom in the amino group and the partially negative oxygen atom in the carbonyl grouping of the peptide courage. The α-helix and β-pleated sheet structures are found in nigh globular and fibrous proteins and they play an of import structural role.

Tertiary Structure

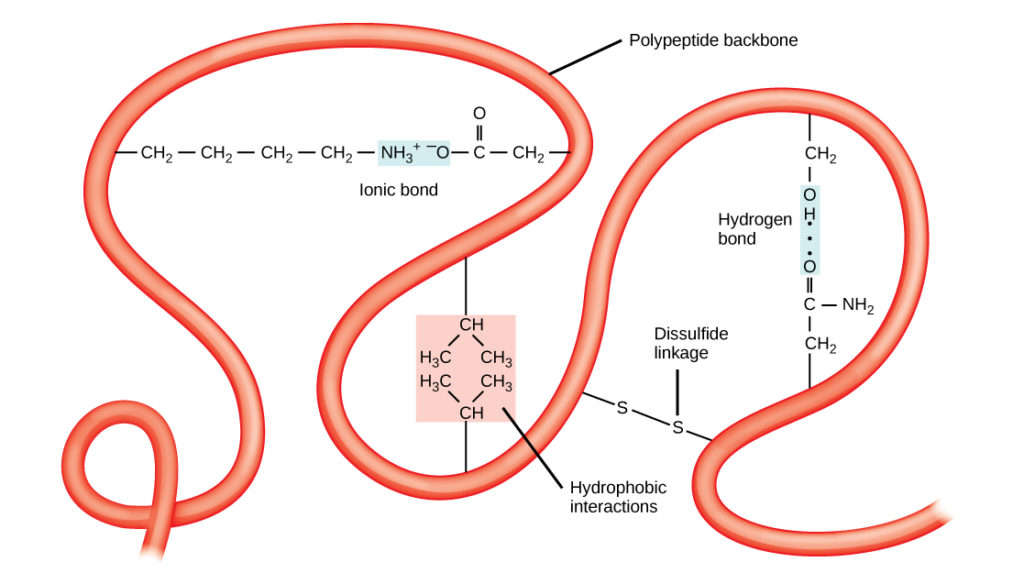

The unique three-dimensional structure of a polypeptide is its 3rd construction (Figure viii). This structure is in part due to chemical interactions at work on the polypeptide chain. Primarily, the interactions amid R groups creates the complex three-dimensional tertiary construction of a protein. The nature of the R groups found in the amino acids involved can annul the formation of the hydrogen bonds described for standard secondary structures. For case, R groups with like charges are repelled by each other and those with dissimilar charges are attracted to each other (ionic bonds). When protein folding takes identify, the hydrophobic R groups of nonpolar amino acids lay in the interior of the protein, whereas the hydrophilic R groups lay on the exterior. The old types of interactions are as well known as hydrophobic interactions. Interaction between cysteine side chains forms disulfide linkages in the presence of oxygen, the just covalent bail forming during protein folding.

Figure 8. The tertiary structure of proteins is determined past a variety of chemical interactions. These include hydrophobic interactions, ionic bonding, hydrogen bonding and disulfide linkages.

All of these interactions, weak and potent, determine the terminal three-dimensional shape of the protein. When a protein loses its iii-dimensional shape, it may no longer be functional.

4th Structure

In nature, some proteins are formed from several polypeptides, likewise known as subunits, and the interaction of these subunits forms the quaternary structure. Weak interactions between the subunits help to stabilize the overall construction. For case, insulin (a globular protein) has a combination of hydrogen bonds and disulfide bonds that cause it to be mostly clumped into a ball shape. Insulin starts out as a unmarried polypeptide and loses some internal sequences in the presence of post-translational modification subsequently the formation of the disulfide linkages that hold the remaining bondage together. Silk (a fibrous protein), however, has aβ-pleated canvas structure that is the result of hydrogen bonding between different chains.

The four levels of poly peptide construction (primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary) are illustrated in Figure 9.

Effigy ix. The four levels of poly peptide structure tin can exist observed in these illustrations. (credit: modification of piece of work past National Human Genome Inquiry Institute)

Denaturation and Protein Folding

Each protein has its own unique sequence and shape that are held together by chemical interactions. If the protein is subject to changes in temperature, pH, or exposure to chemicals, the protein structure may change, losing its shape without losing its master sequence in what is known as denaturation. Denaturation is frequently reversible because the chief construction of the polypeptide is conserved in the process if the denaturing agent is removed, allowing the protein to resume its function. Sometimes denaturation is irreversible, leading to loss of function. One example of irreversible poly peptide denaturation is when an egg is fried. The albumin protein in the liquid egg white is denatured when placed in a hot pan. Non all proteins are denatured at loftier temperatures; for instance, leaner that survive in hot springs have proteins that function at temperatures close to boiling. The tum is as well very acidic, has a low pH, and denatures proteins as part of the digestion process; however, the digestive enzymes of the stomach retain their activity under these conditions.

Poly peptide folding is critical to its function. It was originally idea that the proteins themselves were responsible for the folding process. Only recently was it constitute that oftentimes they receive assistance in the folding process from protein helpers known as chaperones (or chaperonins) that associate with the target protein during the folding process. They deed by preventing aggregation of polypeptides that make up the complete protein construction, and they disassociate from the protein one time the target protein is folded.

Function of Proteins

The primary types and functions of proteins are listed in Table one.

| Table 1. Protein Types and Functions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Blazon | Examples | Functions |

| Digestive Enzymes | Amylase, lipase, pepsin, trypsin | Assistance in digestion of food by catabolizing nutrients into monomeric units |

| Transport | Hemoglobin, albumin | Acquit substances in the blood or lymph throughout the body |

| Structural | Actin, tubulin, keratin | Construct dissimilar structures, similar the cytoskeleton |

| Hormones | Insulin, thyroxine | Coordinate the activity of dissimilar body systems |

| Defense force | Immunoglobulins | Protect the trunk from foreign pathogens |

| Contractile | Actin, myosin | Upshot musculus wrinkle |

| Storage | Legume storage proteins, egg white (albumin) | Provide nourishment in early development of the embryo and the seedling |

Ii special and mutual types of proteins are enzymes and hormones. Enzymes, which are produced by living cells, are catalysts in biochemical reactions (like digestion) and are usually complex or conjugated proteins. Each enzyme is specific for the substrate (a reactant that binds to an enzyme) information technology acts on. The enzyme may assistance in breakdown, rearrangement, or synthesis reactions. Enzymes that break down their substrates are called catabolic enzymes, enzymes that build more circuitous molecules from their substrates are chosen anabolic enzymes, and enzymes that affect the charge per unit of reaction are called catalytic enzymes. It should exist noted that all enzymes increment the charge per unit of reaction and, therefore, are considered to be organic catalysts. An example of an enzyme is salivary amylase, which hydrolyzes its substrate amylose, a component of starch.

Hormones are chemical-signaling molecules, unremarkably pocket-sized proteins or steroids, secreted by endocrine cells that act to command or regulate specific physiological processes, including growth, development, metabolism, and reproduction. For case, insulin is a protein hormone that helps to regulate the blood glucose level.

Proteins have unlike shapes and molecular weights; some proteins are globular in shape whereas others are fibrous in nature. For example, hemoglobin is a globular poly peptide, but collagen, found in our skin, is a fibrous poly peptide. Protein shape is disquisitional to its function, and this shape is maintained by many dissimilar types of chemical bonds. Changes in temperature, pH, and exposure to chemicals may lead to permanent changes in the shape of the poly peptide, leading to loss of function, known as denaturation. All proteins are made up of dissimilar arrangements of the aforementioned 20 types of amino acids.

In Summary: Proteins

Proteins are a class of macromolecules that perform a diverse range of functions for the jail cell. They help in metabolism by providing structural support and by acting equally enzymes, carriers, or hormones. The building blocks of proteins (monomers) are amino acids. Each amino acid has a central carbon that is linked to an amino group, a carboxyl grouping, a hydrogen atom, and an R group or side chain. At that place are 20 normally occurring amino acids, each of which differs in the R group. Each amino acid is linked to its neighbors past a peptide bond. A long chain of amino acids is known equally a polypeptide.

Proteins are organized at four levels: main, secondary, third, and (optional) quaternary. The primary construction is the unique sequence of amino acids. The local folding of the polypeptide to grade structures such as theα helix and β-pleated sheet constitutes the secondary structure. The overall three-dimensional construction is the tertiary structure. When two or more polypeptides combine to form the complete protein structure, the configuration is known every bit the quaternary structure of a protein. Protein shape and part are intricately linked; any change in shape caused by changes in temperature or pH may lead to protein denaturation and a loss in function.

Check Your Understanding

Answer the question(south) below to run across how well you understand the topics covered in the previous section. This short quiz doesnot count toward your form in the class, and you can retake it an unlimited number of times.

Use this quiz to check your understanding and decide whether to (one) written report the previous section further or (ii) move on to the adjacent section.

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-wmopen-biology1/chapter/proteins/

Posted by: cowleslingthe.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Are The Makeups Of Protein"

Post a Comment